ABSTRACT

Dedaub was commissioned to perform a design review for project “Virtuoso”, a possible successor of Liquity v1. Virtuoso aims to provide a fully decentralized yet securely pegged and highly scalable stablecoin.

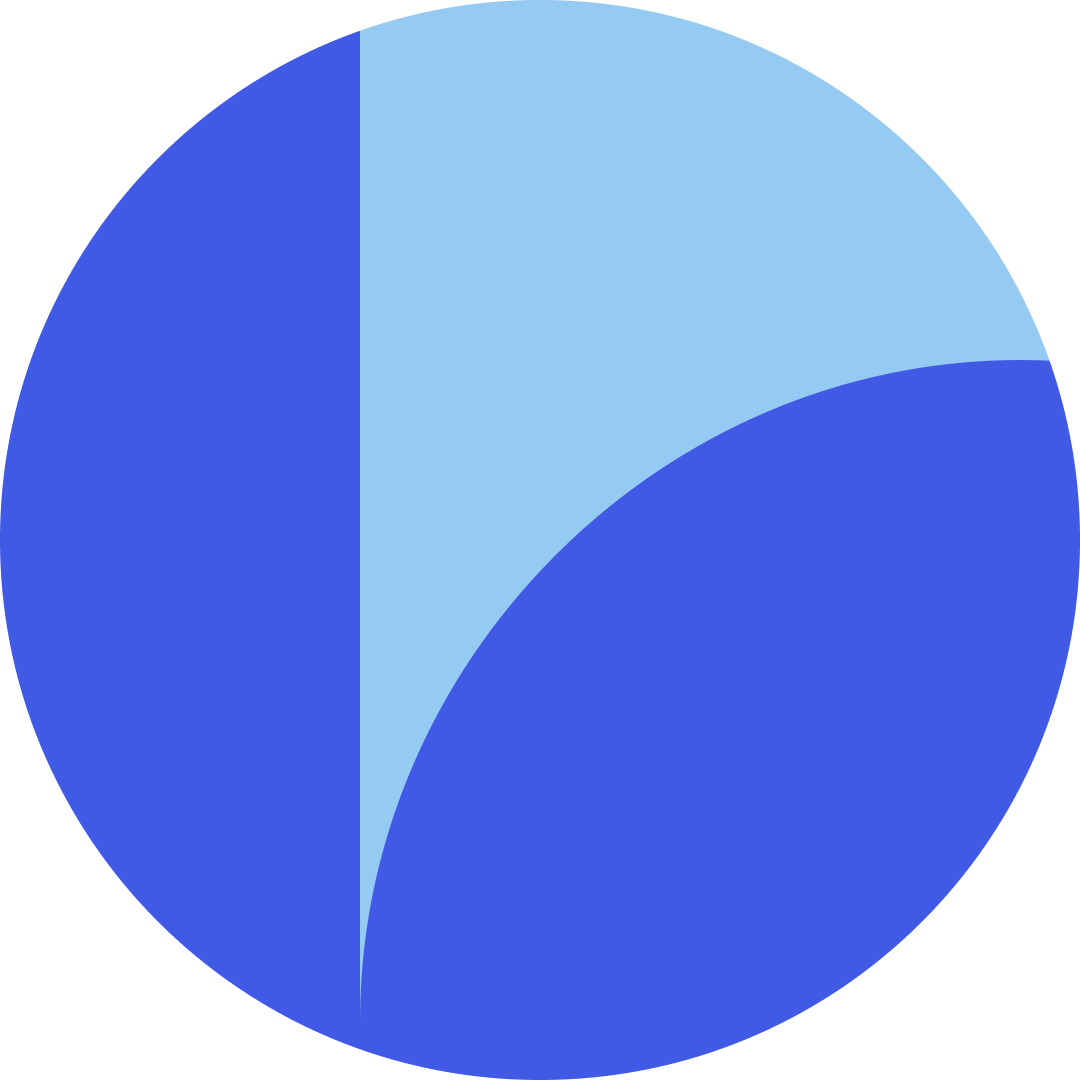

The main idea behind Virtuoso is that the stablecoin is backed by external assets (stETH) and, at the same time, a variety of mechanisms secure the peg. These mechanisms include hedging positions, a stability pool, and over-collateralized borrowing positions (collateralized with the backing token). The different mechanisms appeal to investors with different risk profiles: borrowing positions permit very high leverage (higher than Liquity v1); hedging positions offer relative stability for investors yet a potential for high leverage should losses be incurred—the hedging position acquires higher leverage when ETH price drops (which leads to a lower core value for the position); stability pool deposits are typically collecting yield but can be converted to hedging positions with beneficial terms if exercised.

The protocol defines two separate but interconnected mechanisms: a Reserve, responsible for minting backed stablecoin and protecting the peg, and a borrowing module, quite similar to Liquity v1. The Reserve can be seen as a generalization of the Stability Pool of Liquity v1 and indeed contains a Stability Pool (SP) component that allows replenishing the backing asset if the broader market does not do so quickly enough.

During this design review, the design shifted to a model where the Stability Pool is external to the Reserve, with its assets not counted for Reserve accounting, effectively becoming a third separate component.

PROTOCOL BACKGROUND AND CONSIDERATIONS

The high-level principle that supports the viability of the project is clear:

_The price of stETH in USD will be growing, on average, and the market has confidence in this fact_.

The first part of this assumption is essential for maintaining the stablecoin peg, given the backing asset. The second part is essential for ensuring that there will be hedging depositors that will accept increased leverage in exchange for possible temporary losses. Given that stETH has a ~5% yield, the assumption seems reasonable, barring existential threats to Ethereum.

The protocol is being worked out in significant detail, by a team with top expertise and ability. It is, however, highly complex and it is unclear whether the full complexity is necessary. For instance, it is possible that having three mechanisms backing the peg (instead of just two) is overkill and a significant threat—in terms of both implementation and finance attack surface. Although the design audit focuses on the given design, it is worth considering whether the value of the Stability Pool outweighs such concerns. The value is limited to rapidly restoring the backing ratio (BR) of the Reserve. If, however, the peg is safe, by allowing redemptions from borrowing positions (much like in Liquity v1), it is unclear whether the speed of restoring the backing ratio is crucial.

FOCUS POINTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

We next detail design points on which we want to draw particular attention, since we believe they represent threats or are treated incompletely in the current design.

FOCUS POINT 1:

Redeeming a hedging position (HP) for its principal is not guaranteed.

The whitepaper treats the redemption of an HP for its principal as a guaranteed event, as long as enough time elapses. We point out that there is no mathematical guarantee that there will be enough funds for subsidies to make this property always true. Reasons for this include, at least:

- It is not possible to have predicted in the past the exact amount of premium required to support all future subsidies. The subsidies depend on the current stETH price.

- HPs derived from the Fallback mechanism are not charged premiums. So, by definition, not all HPs can be adequately subsidized.

Since not all positions are redeemable for their principal, there is potential for a bank run, where investors try to exit before others, knowing that the subsidies are not enough for all. For this to happen, the medium- to long-term sentiment regarding the price of stETH has to be negative.

FOCUS POINT 2:

It is unclear how key quantities are defined, as well as how the protocol recovers, when the backing ratio (BR) is 1 or less (issue 43).

The whitepaper is written with the expectation that BR > 1. Key quantities (e.g., “leverage”) are not even defined when the stETH in the Reserve is not enough to back the Reserve-minted vUSD. Even if this is an undesirable situation, it is not realistic to completely discount it. Market sentiment may be negative for significant periods of time. The peg of the stablecoin should be guaranteed in this case, as well as a plan for the protocol to recover should be worked out.

In fact, it is the robustness of the protocol against such pressure that will be the best guarantee that the pressure will never be encountered in practice!

FOCUS POINT 3:

The definition of L2 (and, by extension, BR) is not complete.

(Seemingly addressed during the audit period.)

The whitepaper defines L, the quantity of Reserve-backed vUSD, to include all holdings of the Stability Pool. However, the size of the SP is not bounded and could include arbitrary quantities of vUSD that is backed by borrowing positions and not minted by the Reserve.

It seems that the design is settling on considering the SP a separate component, whose holdings are not part of the Reserve assets/liabilities accounting.

FOCUS POINT 4:

The pricing of HPs should be treated as an intuitive argument, with clear exceptions, and not as strong formal evidence.

The whitepaper prices hedging positions as the sum of a loan and an option. However, this is clearly not a mathematical guarantee, but a simplified calculation, under positive market conditions. The two components are certainly not independent: one cannot perform all actions on the loan without affecting the option, and vice versa. At an extreme, it is certainly not valid to claim that at the time of opening a position (where c = p is the deposited amount), the position is worth c+p.

FOCUS POINT 5:

“Undesired” conditions require more thought. For instance, an HP may not even be redeemable for its core.

The whitepaper focuses extensively on protocol behavior when everything is going well, i.e., BR ≥ CT (i.e., the backing ratio of Reserve-minted vUSD is above a “critical threshold”). Although this is an explicitly-stated goal of the protocol, it is not a guarantee. If users are able to mint vUSD by depositing stETH of equal value, maintaining a high BR is a wish and not an always-valid assumption.

For instance, based on footnote 21, under completely realistic conditions (BR < CT), the protocol may suspend the redemption of HPs for their core. This is a very significant restriction.

Generally, we recommend a lot of thought on protocol operation under adversarial market conditions, and clear statement of invariant properties, even under assumptions. I.e., it should be clear what properties are guaranteed to hold (e.g., “HPs are redeemable for their core”) and under what conditions vs. what properties are goals of the protocol and under what informal assumptions, but are not strictly guaranteed.

FOCUS POINT 6:

Always defending BR > CT is impossible. However, defending the stablecoin peg is possible under broader conditions.

As discussed above, it is not always possible to defend the backing ratio against dropping below the critical threshold, CT, for CT > 1. The protocol intends to produce a fully scalable stablecoin, thus the pressure from large actors can be immense.

Instead, we recommend a much greater emphasis on maintaining the stablecoin peg, as long as the protocol has assets. In this light, a design that allows vUSD redemptions through borrowing troves (e.g., footnote 5 of the whitepaper) seems to offer a valuable guarantee of stability comparable to that of Liquity v1.

FOCUS POINT 7:

Missing frontrunning scenario.

A HA can frontrun a liquidation by opening a new (large) HP before the liquidation, the liquidation will increase R2 and therefore his core, the attacker can claim his core and close his position. If the collateral of the liquidated Trove increased R2 significantly, the attacker’s profit could surpass the premium paid for his position, making this a profitable attack. Besides decreasing the shares of the other HA, this attack is also harmful for the protocol, since the increased core claimed by the adversarial HA could also decrease the BR.

This frontrunning scenario is also related to the discussion here about possible time restrictions when someone tries to close his position. There is a comment there that “Even though the premium should normally prevent users from opening and immediately closing HPs, this might still prevent some unforeseen attack scenarios. One example could be when users open “last resort” HPs when BR < 100% or after it recovers to >100%.”. This frontrunning scenario describes a case where opening and immediately closing a position could be profitable and the premium cannot prevent this.

ABOUT DEDAUB

Dedaub offers significant security expertise combined with cutting-edge program analysis technology to secure some of the most prominent protocols in DeFi. The founders, as well as many of Dedaub’s auditors, have a strong academic research background together with a real-world hacker mentality to secure code. Protocol blockchain developers hire us for our foundational analysis tools and deep expertise in program analysis, reverse engineering, DeFi exploits, cryptography and financial mathematics.